Biology, Physiology of Trauma

Renown scientist Dr. Stephen Porges's...

... Polyvagal theory significantly advanced our understanding of how the nervous system responds to threat, stress and trauma.

Overview of the Autonomic Nervous System

By way of background, the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS), a part of the peripheral nervous system, regulates internal organ functions, such as heart rate, digestion rate and pupil dilation. It also responds to trauma or threat.

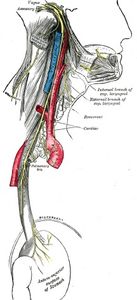

The ANS is usually conceptualized as consisting of two branches, the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. The sympathetic nervous system activates the body, especially during emergencies (“fight-or-flight”); the parasympathetic is calming (“rest-and-digest”). The balance between the two systems is usually said to determine ANS functioning. The parasympathetic nervous system made up of the "dorsal vagal" and the "ventral vagal."

The Ventral Vagal Nerve

Dr. Porges expanded our view of the subject by emphasizing a third factor: the vagus nerve and its role, through its branches, in regulating the heart, face, abdominal viscera and breath. It also communicates with the brain.

The vagus nerve, or more precisely the ventral branch of the vagus nerve, controls the muscles of the face, heart and lungs — parts of the body used to interact with others. This distinctively mammalian system thus fosters what Porges calls “social engagement.”

According to Dr. Porges, social engagement, in turn, tends to “down regulate” (calm) the sympathetic nervous system, and the fight response.

Stated another way, it is in large part through our face/heart/brain connection, mediated by the ventral vagus nerve, that we learn to temper our responses to interpersonal threats and challenges.

The Dorsal Vagus Nerve

The other branch of the vagus, the dorsal vagus, regulates organs below the diaphragm. It is instrumental in activating the “shutdown” of the body seen in cases of overwhelming trauma.

From an evolutionary standpoint, this is a much older part of the nervous system. Something adaptive occurs when the body shuts downs. In the animal kingdom, it fools a predator into thinking his prey is already dead and therefore may be of little interest to the predator. Or it allows the hunted to disassociate from the anticipated pain and harm.

This is true for us humans, too. When encountering a serious threat, disassociation shields us from acutely experiencing the event. Our problems begins afterwards when we are unable to self-regulate our system and begin to live with diminished capacities, fear, and pain.

Recent modalities for healing trauma, such as Somatic Experiencing, use details from Dr. Porges’ description of dorsal and ventral vagal functioning to develop gentle, somatically based strategies for releasing trauma.

psychotherapist physiology of trauma

Copyright © 2022 Somatic Wellsprings - All Rights Reserved.